Monthly Archives: November 2010

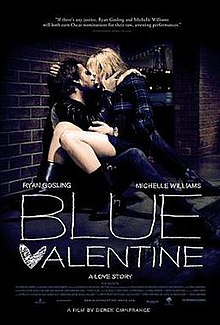

Blue Valentine: Some Feelings Not Suitable for Minors

If you have heard anything at all about Blue Valentine, you’ve likely heard about its controversial NC-17 rating. The film’s rating had film blogs abuzz when the rating was issued a few months ago, particularly after it was announced that the rating would be appealed by the film’s distributor, The Weinstein Company (UPDATE: the rating was eventually overturned). Indeed, when the film played on the first full night of the 2010 Philadelphia Film Festival, the question of whether the rating was or was not deserved dominated discussions before and after the film’s screening.

This is a shame, because Blue Valentine deserves discussion on its own merits. The film, which juxtaposes the first exhilarating days of a relationship with the excruciating death throes of a marriage a handful of years later, benefits from tremendous performances from Ryan Gosling and Michelle Williams,who have established themselves as actors with talent and discretion. The film’s creative team shows remarkable command and control, technically (in its use of non-linear editing and handheld camera) as well as narratively (never providing its audience an “easy out”). Beyond its formal qualities, the production history of Blue Valentine provides an interesting model for independent film production in the contemporary film industry: the script won a grant competition financed by the Chrysler Corporation in 2007 before debuting in competition at Sundance in 2010. Of all the films I saw at the Philadelphia Film Festival, or all the quality films I’ve seen this year, this is, without question, the best, and most interesting.

With that said, the reality is that the controversy over the film’s rating has completely taken over the film’s buzz (and provided The Weinstein Co with some free publicity in the process.) The usual complaints against the MPAA’s arcane and opaque ratings processes have circulated, noting that Blue Valentine‘s sex scenes pale in comparison to representations of sex and violence that frequently grace screens in mall multiplexes. Matthew Thrift’s take is representative of these discussions:

It’s an honest (albeit hardly graphic) representation that garnered the film an NC-17 certificate in the US by the MPAA, it would seem that they’ve no problem with us seeing ever increasing instances of extreme screen violence but two consenting adults having sex in anything more than candle-lit timidity has them fearing for our safety as a society.

As Thrift rightly points out, the sex in Blue Valentine is hardly explicit. It features no “full frontal nudity,” as the saying goes – Gosling’s rear end is shown once, and Williams breasts are exposed only fleetingly. Considered against R-rated sex comedies or thrillers, the film appears quite tame. It seems to me, however, that it is not what we see in Blue Valentine’s traumatic sex scenes that the MPAA has deemed unsuitable for minors. Rather, it is what we feel, and particularly the feelings the film prompts about sex, that the MPAA has cast as inappropriate for viewers under the age of seventeen.

It is really only the film’s final “sex scene” that deviates from standard Hollywood practice. Dean and Cindy, in an effort to escape the pain of their marriage’s inevitable collapse, spend the night in a tacky hotel. Dean wants to have sex with Cindy, but Cindy doesn’t want to have sex with him. Very quickly, it becomes clear that this situation will end badly–Cindy acquiesces not because she’s threatened by Dean in any direct way, but rather as a coping mechanism (there are moments in the film that suggest that Cindy’s father abused her during childhood, which would account for her emotional detachment in this scene). Dean, for his part, can tell she has shut down emotionally and stops–embarrassed and hurt that she has effectively offered her body, but nothing more. The ensuing argument between the two is incredibly sad, but it is also grounded in the best intentions of two characters trying to keep some semblance of “family” in their lives. It is beyond dispute that Dean and Cindy did, in fact, love each other at one point, and even by the end there still is love in their relationship. Blue Valentine is the story of star-crossed lovers in which the stars win and the lovers lose. In other words, the film punctures a notion of romantic love that can overcome all odds, and instead shows a world in which things like “classed notions of success” and “gendered codes of behavior” have soul-crushingly real effects…and affects.

What interests me about Blue Valentine‘s rating controversy is not pointing out the obvious inanity/insanity of Hollywood’s rating system, but thinking through what Blue Valentine‘s rating might tell us about the relationship between adolescence, sexuality and affect in contemporary American culture. It is, after all, only young people who are explicitly barred from seeing the film with an NC-17 rating, and it is in the name of protecting young people that most commercial cinemas will not screen NC-17 films. Young people, who maintain a privileged position in our commercial media landscape, are at the center of nearly all representations of love and sex in commercial media. So what does it mean for American society to “protect” young people from the feelings regarding love and sex that Blue Valentine evokes?

It seems revealing that on September 24, a little more than three weeks before the MPAA handed Blue Valentine its NC-17 rating, Columbia’s The Virginity Hit got a wide release in mall multiplexes nationwide. Taking its cues from Superbad, American Pie, Porky’s and numerous other entrants in the get-laid-or-die-tryin’ formula sweepstakes, the film tells the charming story of real nice guy Matt (Matt Bennett) his fat lunkhead friend (Zack Pearlman), and their conspiracy to secretly videotape Matt’s first sexual experience with his high-school sweetheart Nicole (Nicole Weaver).

After he suspects that Nicole has betrayed him by sleeping with a college guy, Matt is heartbroken. In retaliation, he and Zack plan to distribute the video virally in order to “punish” Nicole’s betrayal. When that plan fails, Matt tries to have sex with Zack’s little sister, a graduate student doing sociological research on adolescent sexual behavior (uhh…what?), and finally, a prostitute. These efforts, of course, all fail until Matt learns something or other about what’s really important, clearing the moral terrain for him to have sex with Nicole. What a happy ending! For the totally sweet bros of The Virginity Hit, sex is not their manifest destiny as red-blooded American boys. It is also currency in their social system, a service to be purchased and rendered, and a product for them to produce, package, and distribute for their own personal gain–a notion, it must be said, that is not the invention of The Virginity Hit but rather the standard script for most representations of sex in popular culture, from Axe Body Spray advertisements to Sex and the City.

I’d argue that this episode illustrates that American attempts to shield young people from the kinds of emotional and psychological discomfort represented in Blue Valentine results in a society in which love and sex can only be viewed as a product to be not only consumed, but also packaged and distributed in exchange for capital (cultural or otherwise.) It is hardly a groundbreaking claim to argue that Hollywood commodifies sex–what I find interesting in this case is the explicit banning of “worthless” sex, of sex that provides neither pleasure nor power. The consequences for a society in which representations of sex that prompt uncomfortable feelings–despair, regret, guilt, or rejection– are considered inappropriate for minors, but representations of sex that unproblematically present it as a commodity–manufactured, distributed, consumed and valued through market processes–are the standard are both real and dramatic. Three days before The Virginity Hit premiered, a first year student at Rutgers University secretly recorded his roommate engaged in sexual behaviors and broadcast them to his peers. Of course, the ensuing tragedy cannot in any way be put in a causal relationship with any film, narrative, or ratings board decision. However, we can consider how media representations of love and sex that elide the possibility for pain, grief, or loss structure our understanding of human sexuality, and limit our capacity to feel at all.