Blog

The radical power of doing your own thing.

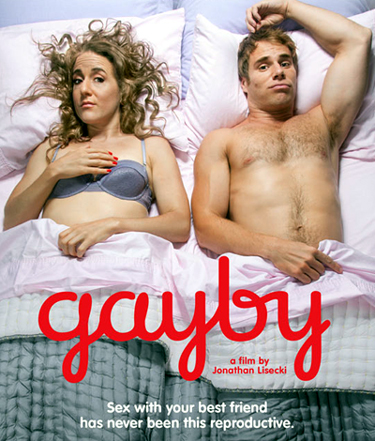

There are many, many things to love about being a member of the Department of Media and Communication, but one of my very favorite perks is the Department’s relationship with the Philadelphia Film Society and the Philadelphia Film Festival, which was held this year in October, and Arcadia students and faculty had the opportunity to see loads of great films there. I wasn’t able to catch as many films there as I’d wanted, but I did get to see some great ones: THE SESSIONS, STEP UP TO THE PLATE, the short THE PROCESSION, HOLY MOTORS and SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK. But perhaps my favorite experience at the festival this year was seeing GAYBY, the lovely little comedy written and directed by Jonathan Lisecki.

Part of what makes GAYBY so charming is how deceptively simple its premise is. Jenn wants to get pregnant, can’t afford fertility treatments or in vitro procedures, so she asks her college best friend Matt to impregnate her the old fashioned way. Matt is gay, hijinks ensue, you can fill in the blanks from there. Except you can’t, exactly–the film is able to avoid and often subvert those well-worn conventions from all of those television sitcoms that have toyed with the scenario since the mid 1990s. It’s not fine cinema, and it’s not trying to be. It’s just a clever and fun movie.

In addition to writing and directing, Lisecki is hilarious as Nelson in GAYBY

Lisecki first made Gayby as a short film (which is where I first heard of it–it won Best Short at the 2010 Philly Film Fest). By 2011 production had begun on the Gayby full-length feature, which premiered at South by Southwest in March 2012, and picked up an Honorable Mention Audience Award for American Independent Film at the Philadelphia Film Festival.

I enjoyed the film itself, but what has kept me thinking about GAYBY for the last month is the process by which the film itself got made. Lisecki told The New York Times that part of his motivation for making the film was his own frustration with the acting parts available for gay men: “I went through a five-year period where I auditioned for these absurdly caricatured versions of the gay best friend,” he told Mekado Murphy in October, “And I thought if this is all I’m going to be allowed to do in this industry, then I have to go create my own work.” But he wasn’t alone in making the film, of course.

As I watched the film’s end credits roll, I noticed a special thanks message to Kickstarter backers, so during the Q&A with Lisecki after the film I asked him about his experience with the crowd-funding service. Lisecki had nothing but positive things to say about the experience–he was able to raise over 16000 to help fund post-production–but what he said about it was somewhat surprising. What was most valuable, he said, was not the people making economic investments in the film, but emotional investments in the film–feeling a sense of ownership of the project, talking about it with their friends, posting about it on social media, and so on. In other words, building a following, a community of support, and a structure of belief around the project was as important as raising the money itself.

The idea of building your own structures through which you could follow your interests that Lesnicki emphasized resonated with my own experience. In high school I killed time with friends by endlessly working on scripting, filming, and editing a movie with nothing but a full-size VHS camcorder. I also built a website, took tons of photographs and wrote cruddy poetry. None of these things were “good,” but they were fun to work on, and the experience helped me in projects I worked on later.

Then, in college, I discovered the Mr. Roboto Project in Pittsburgh, which transformed my life. I remember the first time I walked into the Roboto space, for a benefit show that a high school friend had organized. I had been going to punk/hardcore shows in VFW halls and church basements for a while, but Roboto was different. VFW halls, naturally, had their own idiosyncratic rules about how you might use their space. But Roboto was ours–it was owned and operated by kids in Pittsburgh, and if you wanted to join, all you had to do was put in your twenty bucks. You weren’t at the whims of a landlord or a show promoter. You could promote your own show or host a zine exchange, have a discussion group or screen a film. You could make decisions on how the space was run. Instead of just being a consumer of things, you could experience the power and pleasure of DIY. Like Ian Mackaye recently told Mother Jones, “if you ask for permission, the answer is always no. So I developed a practice of just doing things.”

This is not just possible in dingy underground music venues. A few years ago I was listening to an interview with Judd Apatow on a podcast called The Sound of Young America (now called Bullseye), and was struck by the story of how he broke into the comedy world:

I just love the idea of a teenaged Judd Apatow calling up the Screen Actors Guild and hunting down Weird Al for an interview for his rinky-dink high school radio show.

This, it seems to me, is not all that different from the story of how The Washington Post’s Ezra Klein broke into the world of high-level political commentary. Getting a column in The Washington Post is traditionally the result of high level connections, whether through money or elite Ivy League education. Klein is certainly well-educated–he attended both UC Santa Cruz and UCLA as an undergraduate–but he was not hand-picked for success. When he applied for a position in the campus newspaper, he was turned down. So he began blogging, first on his own and then with other prominent “netroots” figures.

It’s also not all that different from the story of Tavi Gevinson, the young woman who went from fashion blogging at 13 to founding Rookie magazine at age 15. She is now a prominent figure in global fashion, appearing in the pages of The New York Times, at fashion shows, and on television shows like Project Runway. This article in Rookie is a good example of the magazine’s style and attitude.

What do these people have in common? They did not wait to get a job in the industry that they were interested in to start working in that industry. And they didn’t start that work thinking it would immediately turn into something professional–it just helped them build their skills, make connections, and develop their own confidence. Like Apatow says, his high school radio show was “comedy college.”

In my own job as a college professor, I try to make clear to my students that while I am there to help them develop their skills, expand their knowledge, challenge them and build their confidence, I am not going to be enough. No teacher could be. If you are training to be a basketball player, you need to listen to coaches, study opponents, and understand both basketball techniques and tactics. But you can’t just watch film and do drills. You also have to play basketball. So it is the same for my students, who want to be filmmakers, or writers, or designers, or public relations professionals. They need to study, they need to work on their technique. But they also just need to do stuff.

This is why the most rewarding thing I’ve done as a teacher has been advising the students at Loco Magazine. While I do my very best to advise, support, and counsel those students regarding the process of pitching stories, making the most of the online format of the magazine, and promoting their work on social media, the work those students do is entirely of their design. They pitch the stories, make assignments, rigorously edit (with double-blind review!), design and promote the project. This means considerable risk–every issue could be really bad. And since every issue is online, with their names attached to it, it could be embarrassing for a long, long time. But instead, because of these students ability and commitment, they’ve built what I believe to be the best student publication on campus. And they’ve done it entirely on their own.

There is a radical power to sticking your neck out and doing the stuff you want to do. Even if that work is not as good as you wish it could be, the very fact of making your own film, or starting your own radio program, or founding a magazine reinforces a belief that the things you create can be meaningful–that you yourself are meaningful and important and powerful. That is as crucial as any essay, any project, or any mark on a transcript. This is the opportunity we can offer here at Arcadia, and I sincerely hope all of our students will take it.