Blog

Built to Last

https://storify.com/popthought/built-to-last

Sound Tracks: Pop Music through Media

Next semester I’ll be teaching a University Seminar called Sound Tracks: Pop Music through Media, a course that explores the way that the industry that surrounds the production of pop music has shaped the cultural meaning of music itself, and influenced the development of other media forms (Hollywood film, television, video games, and media technology). The course will first consider the structure of the music industry (Unit 1), then examine cultural phenomena like stardom, genre and ideology through pop music (Unit 2), next analyze the interaction between hardware developments like the cassette deck and the iPod on the “software” of the album and the “leaked” single (Unit 3), and finally explore the relationship between pop music and screen media (film, television, and the Internet).

Course description below, after the jump.…

I thought about a lot of things in Paris.

The little liberal arts college that I call home has made a name for itself for its extensive study-abroad programs. A significant majority of our students spend at least a semester abroad, and nearly all of them use their passports as part of an academic experience during their undergraduate career. Students are required to fulfill a “Global Connections” requirement before graduation, which is defined as “a sustained cross-cultural experience.” Something that the University calls “ID courses” are one way students can fulfill the Global Connections requirement without spending a full semester abroad.

When I found out that the Office of International Affairs had approved my partner’s proposal for an ID Course called “Americans in Paris,” I was excited for her. She had previously assisted on a Freshman “Spring Preview” course that traveled to Paris, and was keen to design a course of her own that focused on the American expatriates …

The radical power of doing your own thing.

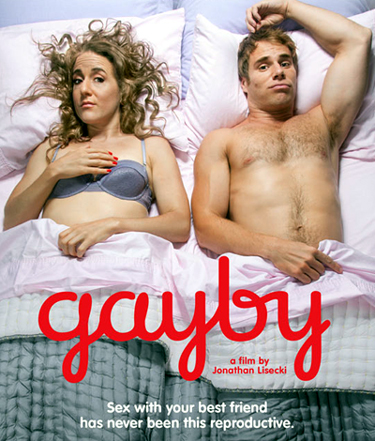

There are many, many things to love about being a member of the Department of Media and Communication, but one of my very favorite perks is the Department’s relationship with the Philadelphia Film Society and the Philadelphia Film Festival, which was held this year in October, and Arcadia students and faculty had the opportunity to see loads of great films there. I wasn’t able to catch as many films there as I’d wanted, but I did get to see some great ones: THE SESSIONS, STEP UP TO THE PLATE, the short THE PROCESSION, HOLY MOTORS and SILVER LININGS PLAYBOOK. But perhaps my favorite experience at the festival this year was seeing GAYBY, the lovely little comedy written and directed by Jonathan Lisecki.

Part of what makes GAYBY so charming is how deceptively simple its premise is. Jenn wants to get pregnant, can’t afford fertility treatments or in vitro procedures, so she asks her college best friend Matt to impregnate her the old fashioned way. Matt is gay, hijinks ensue, you can fill in the blanks from there. Except you can’t, exactly–the film is able to avoid and often subvert those well-worn conventions from all of those television sitcoms that have toyed with the scenario since the mid 1990s. It’s not fine cinema, and it’s not trying to be. It’s just a clever and fun movie.

The Joy of Media Studies

In teaching my undergraduate Media Studies seminar, I often illustrate concepts that students find abstract or complex with examples from pop music, and especially music video. A few weeks ago, I was using a series of clips to run through some dominant concepts in mid-twentieth century media studies, a funny thing happened in my classroom.

I started to play this clip…

…and just as I reached to turn the sound down and start talking about QD Leavis, my students started singing. All of them. Loudly.

Mapping our Lives with College Memes

Unless you were attending Deep Springs College and were too busy herding cattle by day and reading Nietzsche by night this spring to notice, your campus probably had its own “College Memes” page on Facebook. My own alma mater, the University of Miami (woosh, woosh) has several FB meme pages, each with approximately 2000 likes (this for a school with about 10,000 undergrads).

The Huffington Post, itself the newspaper equivalent of an internet meme in some ways, covered the phenomenon this February, after multiple college-centric meme figures had established themselves nationwide–Sheltered College Freshman, Lazy College Senior, Scumbag Steve, etc.

These College Memes pages are essentially all the same: you have your standard “One does not simply walk into [place where students routinely walk into]”; your various jokes about the quality of dorms, dining hall food, or campus social life; some scattered laments on the order of “Oh, my school is so full of hipsters!”; and the occasional “HAI, I don’t take my assignments seriously: LOL!”¹

The New Yorker, Seinfeld, and Intertextual Pleasures

A friend of mine posted this cartoon from The New Yorker’s caption contest on Facebook the other day, accompanied by the comment: “Holy shit! They finally did it! And yes, I submitted ‘My wife is a slut.'”

This struck me as weird, because a) It’s sort of an unremarkable cartoon b) I had no idea this friend cared about New Yorker caption contests (I thought that was just Roger Ebert?) and c) the incongruous ‘shock’ misogyny coming from him.

Future Heads in Media Studies

The October issue of PMLA, the official publication of the Modern Language Association, was among my favorite reads of the year. The special issue on “Literary Criticism for the Twenty-First Century,” however, has held top-of-the-coffee-table status for three strong months now. One of the reasons why, aside from the general quality of the scholarship, is what Jonathan Culler calls in the introductory essay “a motif of return.” One of my major research areas is the function of nostalgia–the much-maligned practice of mournfully looking backward that, in my work, I argue can be utilized for diverse and overlapping purposes. Far from being ahistorical, I argue elsewhere, nostalgia tells us about our affective relationships, which are always historical relationships.

It’s perhaps natural that literary studies would get a little nostalgic. Literature and literary scholarship are fascinated with the past. The discipline itself is derived from the tradition of the scribes charged with cataloging the history of their society. Consider its titanic figures–Homer, Shakespeare, Balzac, Hegel, Marx, Twain, Dickinson, Ellison — even literary studies after the age of critical theory has found itself ever drawn to the past. This is, of course, a great strength. One of literary studies’ primary functions is to retain, reexamine, and recontextualize the culture of past societies, and it utilizes its past to think through problems of the present. Retrospection does not equal regression, and many of the best works of criticism, critical theory, and literary analysis have profited from looking back over past historical developments (Foucault’s The Birth of the Clinic), past texts (Fiedler’s “Come Back to the Raft Ag’in, Huck Honey!”) or past figures (Holly Jackson’s work on Emma Dunham Kelley) . As such, the motif of return that Culler notes in his introduction comes as no real surprise.

But, I found myself wondering while reading the issue, what about media studies? For all of literary studies’ interest in its past, looking backward is much more taboo in the realm of media studies. A special issue of Screen or Cinema Journal subtitled “The Future of Media Studies” would, I’d wager, feature much less retrospection. Whether it is the discussion on social media networks, panels at the recent Society for Cinema and Media Studies convention, or job listings for new professorships, the emphasis in media studies certainly does not seem to lay in silent cinema, the industrial history of radio, or music archivists, but rather sexy fields like new media and digital humanities. This is, after all, the same attitude that has allows so much of film and television history to go unarchived, and reflected in something so basic as the Facebook News Feed or Twitter Stream, which updates constantly but allows little easy access to past records.

So how might we think about “the future of media studies”? Frankly, I’m not sure. David Gauntlett has issued a brave attempt here, though I think the 1.0 vs 2.0 dichotomy is one that breaks down under close scrutiny, and truly, one can hardly consider 2.0 to represent “the future” when it actually more closely approximates “the present” or perhaps even “the 1990s” (and, as one of the 1990s primary advocates, I say that without malice).