Back to the Fifties – Film and Pop Music in the Re-Generation, released in July 2015 by Oxford University Press, is the first sustained academic analysis of fifties nostalgia in American popular culture in the 1970s and 1980s. It is available through IndieBound, Amazon, and Barnes and Noble.

As of late 2016, the book has been cited in multiple popular outlets, and was named one of Buzzfeed‘s Best Music Books of 2015. In addition, the book has been favorably reviewed in both academic and popular publications, including PopMatters, The International Media and Nostalgia Network, the German academic journal H/Soz/Kult, and the journal Music, Sound, & the Moving Image.

Members of the Promotion and Tenure Committee can access the book HERE with the password found in my cover letter.

Brief description below:

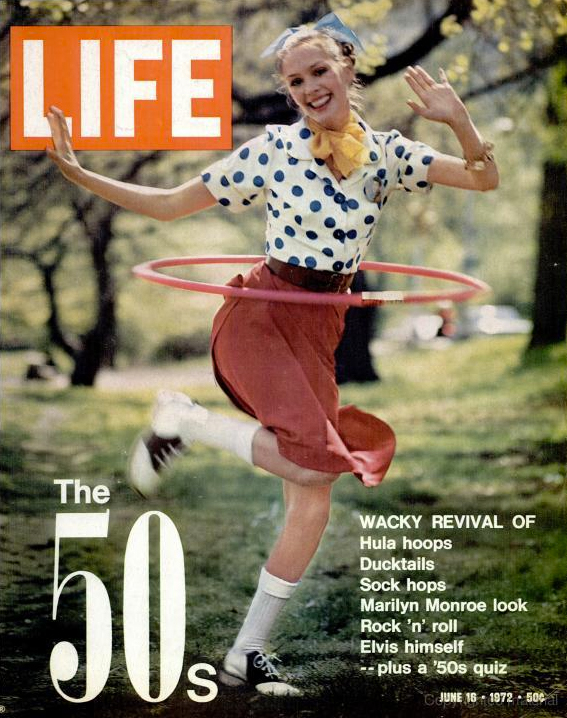

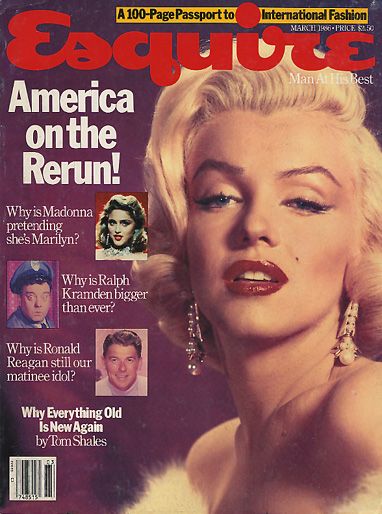

As the increasingly corporatized entertainment industries in America developed synergistic marketing and production practices they both enthusiastically embraced the Fifties. Hollywood produced a slew of nostalgia films (American Graffiti, Porky’s, Back to the Future, Blue Velvet and Hairspray, among many more) and found new markets for 1950s films via cable television and video rental. Simultaneously, pop music mined its own past through the “Golden Oldies” radio format and revival concerts. Affection for 1950s pop music stretched from the top of the charts (Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll”) to punk rock clubs (The Stray Cats’ rockabilly revival). Working collaboratively, the film and music industries converged to bring fifties nostalgia to Hollywood soundtrack albums (Grease, Dirty Dancing) and the burgeoning genre of music videos (Madonna’s “Material Girl,” John Cougar’s “Jack & Diane”).

Those that have discussed fifties nostalgia in the Reagan Era nearly always point to the development of blockbuster economics in the entertainment industries and the rising tide of neo-conservatism as easy explanations. By contrast, my work notes how fifties nostalgia texts proliferated in subcultures as well as blockbusters, and that the visions of the fifties these texts offered were far from homogenous. Even the brief selection of texts mentioned in the previous paragraph reveals the diverse political and social uses of nostalgia in the Reagan Era. My work reveals how “the fifties” functioned in the Reagan Era as a set of unstable signifiers whose meanings were under intense negotiation and struggle, not an ossified concept with discrete political function .Thus Back to the Fifties both complicates and transcends standard diagnoses of the political function of nostalgia in popular media, and sheds new light on the crucial role it continues to play in contemporary politics and culture.

Breaking from the dominant wisdom that casts the nostalgia cycle as wholly defined by Ronald Reagan’s politics or the rise of postmodernism, Back to the Fifties reveals how pop nostalgia from 1973 to 1988 was utilized by a range of audiences for diverse and often competing agendas. Nostalgia in films from American Graffiti to Hairspray and popular music from Sha Na Na to Madonna shaped—and was shaped by—the complex social, political and cultural conditions of the Reagan Era. By closely examining the ways that “the Fifties” were remade and recalled, Back to the Fifties explores how cultural memory is shaped by popular culture and vice versa.

There are several key additions Back to the Fifties offers to extant scholarship:

First, it contributes to an overdue reconsideration of the historical period between the end of the Vietnam War and the fall of the Berlin Wall. All too often, media studies has treated this period as if it were wholly defined by Reaganism in politics and blockbusters in media industries. While there is no doubt that neoconservatism was an enormous political force in the 1980s, the decade also saw many elements of movements for social justice, feminism, gay rights, and environmentalism enter the mainstream. While the major media industries became increasingly corporatized, the 1980s also saw a boom in independent filmmaking, college radio, post-punk and hip hop. The rise of Reaganism was neither universal nor unchallenged in the 1970s and 1980s, and the same can be said of the rise of blockbuster economics in American film and pop music.

Second, it brings a fresh perspective to the evaluation of nostalgia as a whole, and fifties nostalgia in particular. Among academics, nostalgia has drawn almost universal disdain over the last thirty years. Its association with Reaganism has caused many to identify fifties nostalgia as an impulse to undo the social and political reforms of the Great Society and the Counterculture. Meanwhile, theorists (most notably David Harvey and Fredric Jameson) describe nostalgia in postmodern society as a distortion of the past, a practice that mystifies the material and historical realities of capitalist exploitation. These perspectives have dominated scholarship on nostalgia since the mid-1980s. Thus, a simple critical calculus has emerged: “the 1980s” = “Reaganism” = “fifties nostalgia” = “loss of historical consciousness” = “regressive politics.” In my work I seek to complicate those too-simple equivalencies. Clearly, fifties nostalgia in film and pop music was part of the cultural positioning that cleared cultural terrain for the rise of neo-conservatism, but it was also utilized by diverse populations for competing political interests in ways that exceed the Reagan-centric view of much scholarship on the 1970s and 1980s.

Finally, this study addresses crucial emerging concerns in film and media studies. As a proliferation of new technologies makes available an ever-expanding archive of films, television shows, music, and other texts, it becomes vital to understand how texts move through history, within history, and across different media. The remediation and circulation of cultural texts will increasingly shape American cultural memory, and future iterations of those texts—re-released, repositioned and re-booted—will continue to operate in complex ideological ways. Tracing the development of practices of allusion and homage in Reagan-Era culture, this study bridges an important gap between more conventional film studies and new work on sampling and remixing.